We’re always experiencing history now. Few grasp this concept like Alex Cox, who frequently eschews the traditional idea of “historical accuracy” in favor of something we might pretentiously refer to as historical truth. In 1986’s Sid and Nancy, a bunch of kids meet the title character just outside New York City, and when they hear his name — “Sid Vicious” — they immediately scatter. That never happened in real life, but the metaphorical depiction of Sid’s living legend trumps the facts because it actually tells the real story more effectively in film. The more all-encompassing example is 1987’s Walker, Cox’s searing indictment of America’s quasi-colonialist mindset toward Nicaragua. Walker, set in 1853, is full of intentional anachronisms in the form of modern items — helicopters, automatic rifles, Newsweek — that weren’t around at the time. If you presume this device might take you out of the action of 1853, you’re exactly right — and it more or less plants you in Nicaragua in the 1980s, where much the same U.S. meddling would spur the Contra War for more than a decade.

We’re always experiencing history now. Few grasp this concept like Alex Cox, who frequently eschews the traditional idea of “historical accuracy” in favor of something we might pretentiously refer to as historical truth. In 1986’s Sid and Nancy, a bunch of kids meet the title character just outside New York City, and when they hear his name — “Sid Vicious” — they immediately scatter. That never happened in real life, but the metaphorical depiction of Sid’s living legend trumps the facts because it actually tells the real story more effectively in film. The more all-encompassing example is 1987’s Walker, Cox’s searing indictment of America’s quasi-colonialist mindset toward Nicaragua. Walker, set in 1853, is full of intentional anachronisms in the form of modern items — helicopters, automatic rifles, Newsweek — that weren’t around at the time. If you presume this device might take you out of the action of 1853, you’re exactly right — and it more or less plants you in Nicaragua in the 1980s, where much the same U.S. meddling would spur the Contra War for more than a decade.

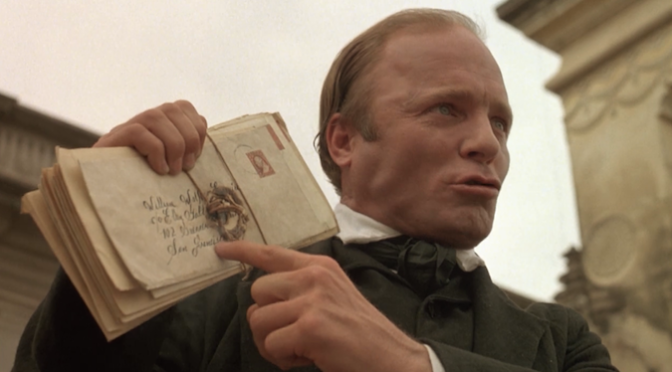

Tombstone Rashomon, Cox’s latest, is in many ways a logical extension of this view of history as inextricable from the present. The title somewhat bluntly particularizes the story at hand: this is the tale of the famous Gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, told in the kaleidoscopic style of Akira Kurosawa’s seminal Rashomon. The tale of this shootout — dubbed on its exhaustively-detailed Wikipedia page as “the most famous shootout in the history of the American Wild West” — has been told in film a hundred different ways already, most notably in John Ford’s My Darling Clementine (1946), John Sturges’s Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), and George Cosmatos’s Tombstone (1993). All of these technically depict the same event, but the varying degrees of accuracy and divergence speaks to Cox’s point: short of being present in Tombstone at about 3:00 p.m. on October 26, 1881, the vast majority of what we “know” about this event comes from its depiction in popular culture.