“How would you feel if I shaved off my mustache?” So begins Emmanuel Carrère’s 2005 film La moustache, a dark and heartbreaking investigation of madness and identity. Marc has worn his upper-lip rag for the past 15 years, as his wife points out, so it might be a little strange if he shaves it off. But shave he does, whimsically, excitedly – and yet no one notices, not his wife nor his friends. In fact, as Marc’s wife tells him in a state of confusion, he has never had a mustache at all in the past 15 years…

Watching La moustache descend from that point onwards is not a task that will result in immediate satisfaction (it may, however, result in an immediate WTF). Marc says that surely their friends will vouch for his facial hair…leading Marc’s wife to inform him that the friends of whom he speaks are also nonexistent. Marc references his parents…and Marc’s wife slowly and cautiously reminds him that his father has been dead for years. Marc soon runs off to Hong Kong to get away from the crumbling world around him.

My interpretation leans much more to the abstract side, as I suspect most interpretations must. You could argue easily enough that a portion (or two, or three) of the fractured film is a dream or a hallucination on Marc’s part, or that the entire thing is imagined. You could just as easily argue that Marc is eminently sane and that an elaborate ruse à la The Game has been constructed by his wife, friends, parents, whoever. It’s respectable that Carrère (who first wrote La moustache as a novel) was able to build something very obviously open to warring readings, but the film as a whole begs a more involved interpretation; it nearly demands you come up with a theory and stick to it, otherwise La mustache just sits uncomfortably like an undigested meal.

While the whole movie is perplexing, the Hong Kong Star Ferry sequence is possibly the most eyebrow-raising: Marc is shown going back and forth on the ferry, arriving, departing, paying for his ticket, moving through the turnstiles, facing one way, facing the next, over and over. Is this a part of his actual existence, or at the very least a representation of how lonely he is? If so, the first chunk of the film could act as a construct wherein Marc has a loving wife, friends, a home, a life. Changing one element of this carefully constructed fantasy (i.e. shaving his mustache off) forces the entire house of cards down. Systems resist change by their very nature, and Marc’s fantasy is upset by a simple lack of hair on his face. He tries to hold onto this – going so far as to dig through the trash to retrieve the remnants of his mustache – but the change is irreparable.

Marc writes a postcard to his wife from Hong Kong, stating that he does not trust his own eyes but only what he sees through the eyes of his wife. At the end of the film, when Marc’s wife is inexplicably present in Hong Kong as if none of the previous conundrums had occurred, Marc disposes of the postcard that he never mailed. Perhaps he has found a new way to make his fantasy work by imagining his wife with him in Hong Kong, and he discards the postcard upon the realization that the original fantasy clashes with the new one.

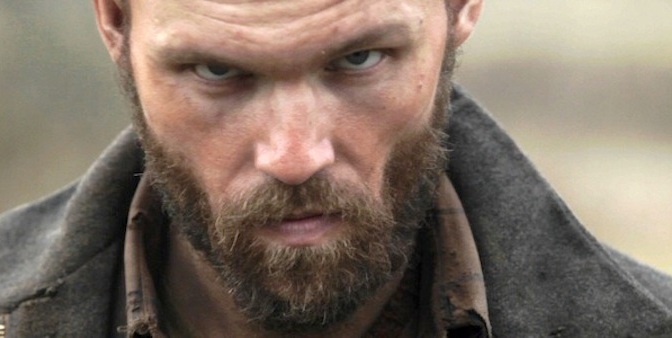

This could very well be a weak interpretation of the first 95% of the film, but I think it’s one that lends the last 5% a particular beauty. Fully-bearded Hong Kong Marc asks his wife “How would you feel if I shaved off my mustache?”, and when he does it this time around she smiles, compliments him on the change, and invites him into bed. His efforts at change within such a lonely existence were met with impossible resistance over the course of the first acts of the film, obstacles that he alone had to endure and overcome. His pain, his conflicted sense of self, the overpowering sense that no one in the entire world is on his side – all of it seems to melt away when his wife recognizes the change that he has enacted.

Your reading may be very different. The fact remains that La moustache is a weird little movie, and one that will undoubtedly get you thinking. Vincent Lindon is fantastic as Marc, and his performance is one of the few indelible elements in a story about transformation of the self.