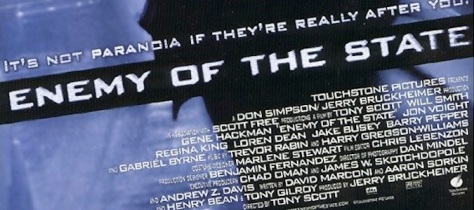

Wait a minute – Aaron Sorkin wrote Enemy of the State? Before we get too deep into false advertising here, let it be known that “rewrites” and “script edits” are terms that are extremely broad and ill-defined in most cases. Yes, Sorkin was brought on for rewrites of the Enemy of the State script by David Marconi; no, it’s not clear how much of the film is “his”, at least not in any explicit way. Sorkin presently has no credit for his work on the film, no listing on IMDb or anywhere else, although an early poster (later redacted) did feature his name right after Marconi’s:

“Written by David Marconi AND Aaron Sorkin AND Henry Bean AND Tony Gilroy” – phew. That many cooks in the kitchen usually isn’t a good sign – maybe bringing to mind Stanley Kubrick’s quote about one man writing a novel, one man writing a symphony, and one man making a film – but Sorkin’s name would eventually be struck, as would Bean’s and Gilroy’s, and Sorkin’s reputation as a controlling “sole credit” scriptwriter would presumably grow from there.

It’s not fair to Marconi (or to Sorkin, for that matter) to play Which Parts of Enemy of the State Did Aaron Sorkin Write?, fun as that game may be. The film, which stars Will Smith as a well-meaning lawyer wrapped up in an NSA intelligence scandal, doesn’t have any scenes that are overtly or glaringly “Sorkin scenes” – we don’t suddenly have any West Wing-style walk-and-talk banter sprinkled in among the action of the script. We do, however, have some sentiments that are undeniably Sorkin-esque. Enemy of the State is straightforward drama in that people want things, these wants prevent other people from getting what they want, and the game of wits continues until someone wins. That makes it sound incredibly boring, so the injection of a timely theme – the sanctity of privacy, the limitations of the American government with regards to surveillance – always helps.

But a primary reason that Enemy of the State fits here is because of another timely theme it brings up: that of credit where credit is due among Hollywood writers and writers in general. I was content to watch Enemy of the State as something tangential to an Aaron Sorkin Writer Series, acknowledging the smallish connection as a coincidence more than anything else. He even made it onto one of the posters – how amusing. But as I watched I found myself waiting for Gene Hackman, another poster presence right there alongside Will Smith – and I was essentially waiting until the last half-hour of the film. He’s not a big part of the plot, although he happens to be there when all the big stuff goes down. His introduction into the events of the film is not jarring or ill-conceived, but it never seems entirely necessary, either. He’s Gene Hackman, one of the most recognized and prolific actors around – and one can’t help but think that this is why he’s so prominently placed when the credit for Enemy of the State is being doled out.

It’s easy to take that logic further, too. Take poor Gabriel Byrne, a truly phenomenal actor resigned to one single scene in Enemy of the State that’s more of a cameo than an actual role. And look! There he is on the posters and in the credits at the beginning of the film, plain as day. Did he do more on work on the film in that one short scene than Sorkin did in his few weeks of writing? Is it possible to even measure the work an actor does alongside the work a writer does?

Enemy of the State calls to mind some classic films that deal with similar themes of privacy and the lives of others, and the movie is enjoyable enough to watch without having to fault it for failing to join those classics. The film it most readily calls to mind is The Conversation, in which Gene Hackman plays an awkward, bespectacled, raincoated surveillance whiz very similar to his character here. That’s a good example of how a very singularly-minded movie – written, produced, and directed entirely by Francis Ford Coppola – can still be positively brilliant, and it’s the kind of film that frankly makes the conglomerate of people behind Enemy of the State look a bit ineffective. Again, the questions it raises about privacy and “our information” are certainly important. We might think about Enemy of the State as a work of art, too, sort of allowing it the benefit of the doubt over other late-’90s action thrillers, and that might in turn allow consideration of “their information” and whether or not the stuff coming back the other way – artistic credit, for example – is actually the whole truth.

Meantime, let’s enhance:

2 thoughts on “Enemy of the State (1998)”