I respect the hell out of Ben Wheatley for his drive to make new film. A good 90% of what he’s done, for better or worse, is actual original cinema — not an adaptation of a beloved novel, not a bastardization of a classic film, not a superhero flick that takes bits and pieces from comic books and cobbles them together into a weak installment of some neverending box-office-driven franchise. A Field in England and Sightseers are sort of the pinnacle of this criteria for Wheatley, with Field as a particular achievement — weird as hell, quite unlike anything you’ve seen to date, but importantly a cohesive experience that you can mine for deeper meaning and rewatch ad nauseam without feeling like you’ve exhausted it. Field does more with five or six actors and a muddy pasture than most movies do with $250 million, and so the prospect of Wheatley returning to ragtag roots with his latest film In the Earth was a promising one.

This is largely due to his most recent efforts: a workmanlike remake of Hitchcock’s Rebecca this past year, in which Armie Hammer wore the same yellow suit in like nine different scenes; High-Rise in 2016, an ultimately joyless adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s novel; and Free Fire, an original movie which zips along on first watch and positively drags on subsequent viewings. If each of these films was successively bigger — in budget terms, but also in scope — they also felt less and less like the scrappy Wheatley who made A Field in England in 12 days on just £300,000.

As is the case with the work of many a cinematic genius, the filmography of Orson Welles is especially revealing when considered as a whole. Hits, flops, stretches of obsession, gaps of inactivity, passion projects and moneygrabs — in some ways this kind of retrospective review can tell us more about the filmmaker than the films themselves. It’s the “God’s-eye view,” to steal the name of an aerial shot favored by Welles, and it serves to highlight the ideas that the writer/director would experiment with, return to, or transform entirely in successive efforts. The other edge of the sword, of course, is that each individual film inexorably loses something when viewed alongside a slew of cinema which may otherwise share little by way of plot, theme, style or cultural impact.

As is the case with the work of many a cinematic genius, the filmography of Orson Welles is especially revealing when considered as a whole. Hits, flops, stretches of obsession, gaps of inactivity, passion projects and moneygrabs — in some ways this kind of retrospective review can tell us more about the filmmaker than the films themselves. It’s the “God’s-eye view,” to steal the name of an aerial shot favored by Welles, and it serves to highlight the ideas that the writer/director would experiment with, return to, or transform entirely in successive efforts. The other edge of the sword, of course, is that each individual film inexorably loses something when viewed alongside a slew of cinema which may otherwise share little by way of plot, theme, style or cultural impact.

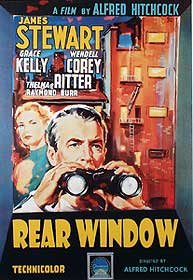

Alfred Hitchcock was no stranger to the optical point-of-view shot, inserting a camera into the heads of his characters in nearly every film throughout his career. The Master of Suspense knew that this shortcut to conveying a character’s experience could be a powerful tool if used artfully. In Vertigo, this artfulness resulted in one of the greatest POV shots of all time, the discombobulating push-in-zoom-out (technically a “dolly zoom”) that simultaneously suggests our hero’s unbalanced frame of mind. More importantly, Hitchcock routinely tied these POV shot choices to significant narrative moments. In Vertigo this served to heighten the most intense action scenes by placing us directly in the action; elsewhere, the POV shot served to convey vital information, revelations, twists and — you guessed it! — suspense:

Alfred Hitchcock was no stranger to the optical point-of-view shot, inserting a camera into the heads of his characters in nearly every film throughout his career. The Master of Suspense knew that this shortcut to conveying a character’s experience could be a powerful tool if used artfully. In Vertigo, this artfulness resulted in one of the greatest POV shots of all time, the discombobulating push-in-zoom-out (technically a “dolly zoom”) that simultaneously suggests our hero’s unbalanced frame of mind. More importantly, Hitchcock routinely tied these POV shot choices to significant narrative moments. In Vertigo this served to heighten the most intense action scenes by placing us directly in the action; elsewhere, the POV shot served to convey vital information, revelations, twists and — you guessed it! — suspense: