Art ages. The second a book hits the shelf, a movie hits the cinema, a painting hits the exhibit or a song hits the radio, that art is in some ways locked into that time period forever. Maybe as time passes that art ages poorly and is sentenced to oblivion — like, say, a racist Donald Duck cartoon or two — regardless of whether it was deemed appropriate or entertaining at the time of publication. Maybe as time passes that art does the opposite, somehow seems more fitting for the current time rather than the time in which it was published, which can often be a hallmark of good sci-fi art (like the original Westworld movie) or good political art (like the V for Vendetta comic) or both (like 1984). But sometimes it’s not so simple. Some art — like The Birdcage — remains both a product of its time and perfectly fit for the future.

Art ages. The second a book hits the shelf, a movie hits the cinema, a painting hits the exhibit or a song hits the radio, that art is in some ways locked into that time period forever. Maybe as time passes that art ages poorly and is sentenced to oblivion — like, say, a racist Donald Duck cartoon or two — regardless of whether it was deemed appropriate or entertaining at the time of publication. Maybe as time passes that art does the opposite, somehow seems more fitting for the current time rather than the time in which it was published, which can often be a hallmark of good sci-fi art (like the original Westworld movie) or good political art (like the V for Vendetta comic) or both (like 1984). But sometimes it’s not so simple. Some art — like The Birdcage — remains both a product of its time and perfectly fit for the future.

This is not an automatic compliment, even in the case of a film as funny and as culturally significant as this one. It’s impossible to rewatch Birdcage — pitched as a somewhat innocent laugh-a-minute comedy and little else — and not think about how the same movie would be made today, what might be changed, what might be emphasized or removed entirely. Today, discussion of the movie must start and end with the way gay or bisexual characters are represented in the film.

You could call Roma the most colorful black-and-white film ever made. After the Centerpiece screening at the 56th New York Film Festival, writer/director Alfonso Cuarón noted how important the visual presentation was to the overall effect of the movie. Crucial among his points was that this black-and-white is “not a nostalgic black-and-white” but instead “modern” and “pristine,” disabusing the viewer of the notion that this tale is unfolding in a long-forgotten place or time. Despite being assured throughout the film that the place is Mexico City and the year is 1971, Roma simultaneously manages to assure you that what’s happening is happening here and now.

You could call Roma the most colorful black-and-white film ever made. After the Centerpiece screening at the 56th New York Film Festival, writer/director Alfonso Cuarón noted how important the visual presentation was to the overall effect of the movie. Crucial among his points was that this black-and-white is “not a nostalgic black-and-white” but instead “modern” and “pristine,” disabusing the viewer of the notion that this tale is unfolding in a long-forgotten place or time. Despite being assured throughout the film that the place is Mexico City and the year is 1971, Roma simultaneously manages to assure you that what’s happening is happening here and now.

Charley Varrick is one lucky guy. Odd, maybe, to associate “luck” with a man who botches a robbery and gets his wife killed, and odder still once he discovers that the money he does get away with belongs to the ruthless Mafia. Over the course of Charley Varrick poor Charley buries his wife, runs from the police, runs from the Mafia, loses his partner, loses his house, loses his plane, and spends a heck of a lot of time contending with the incompetence of others. Traditionally we call the person in this string of situations “unlucky.”

Charley Varrick is one lucky guy. Odd, maybe, to associate “luck” with a man who botches a robbery and gets his wife killed, and odder still once he discovers that the money he does get away with belongs to the ruthless Mafia. Over the course of Charley Varrick poor Charley buries his wife, runs from the police, runs from the Mafia, loses his partner, loses his house, loses his plane, and spends a heck of a lot of time contending with the incompetence of others. Traditionally we call the person in this string of situations “unlucky.”

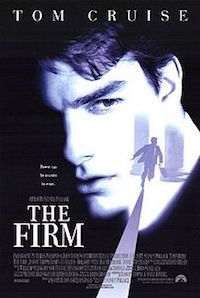

Just now I googled “Tom Cruise best roles”, “Tom Cruise worst roles”, “Tom Cruise best movies” and “Tom Cruise worst movies”, partially because I’m interested to see where his role as Mitch McDeere in The Firm lands and partially because my boredom has reached carrying capacity. I found, unsurprisingly, that the internet does that thing where it reaches consensus about certain things being “good” and certain things being “bad”, which in this case is sometimes inarguable (

Just now I googled “Tom Cruise best roles”, “Tom Cruise worst roles”, “Tom Cruise best movies” and “Tom Cruise worst movies”, partially because I’m interested to see where his role as Mitch McDeere in The Firm lands and partially because my boredom has reached carrying capacity. I found, unsurprisingly, that the internet does that thing where it reaches consensus about certain things being “good” and certain things being “bad”, which in this case is sometimes inarguable (