Executing a Writer Series on Alan Moore would seem especially self-defeating. The idea is possibly even offensive to the man himself, he having gone to great lengths to distance himself from the film adaptations of his comics. He’s had his name stricken from credits and movie posters, declined any input or involvement throughout production and beyond, and even claims to have never seen any of the film versions of his stories. Furthermore, the dude literally writes comics in such a way that they are inherently resistant to any other medium. He doesn’t do this just to be a jerk, but rather to show what comics can do that other mediums cannot.

And From Hell is the perfect example of that, both in its original comic form and in comparison to the 2001 Hughes Brothers film. Most know Moore for his most popular works Watchmen and V for Vendetta, for his brilliant Batman/Joker book The Killing Joke, for creating original characters like John Constantine and breathing new life into previously-thought-useless ones like Swamp Thing. If you’ve read From Hell, though, you know what Moore is truly capable of as a writer.

The differences between comic and film are in this instance numerous and well-documented. The general story is the same: Jack the Ripper tears through a clammy version of Whitechapel, evading capture and stirring a terrible fervor at the same time. He’s pursued to the fullest by Inspector Abberline, who himself is pulled into darkness upon realizing just how inferior that full pursuit really is. Major characters like Marie Kelly, Jack’s fifth victim, are carried over in name if not in character. Nearly everything else is different, though, primarily the treatment of the story as a mystery rather than a true exploration of murder. Gone are important comic characters like the psychic Robert Lees, although that historical character is in fact portrayed on film by Donald Sutherland in the Sherlock Holmes story Murder by Decree, which lies somewhere between the FH comic and the FH movie on the spectrum of Fictional Tales of Jack the Ripper. Come to think of it, Johnny Depp’s Abberline seems to have taken more than a few cues from Sherlock himself, what with the opium addiction and his slightly-condescending treatment of his sidekick Watson Godley.

Some of the disparity can be chalked up to Moore’s “only possible in comics” mantra, just as some can simply be chalked up to Hollywood production idiocy. All of these differences are charted between the efforts of CCLaP, IMDb, Filmwerk, a page-to-screen examination in this volume of Studies in Comics, and a dozen other pieces across the internet. Greg Carpenter’s 3-part series “Delivering the Twentieth Century“, though admittedly unconcerned with the film version, is a must-read analysis of Moore’s masterpiece.

Carpenter touches on the only one of those differences we’re concerned with today, the single most unforgivable change in the Hughes’ adaptation, the one that misses a massive opportunity in visual storytelling and disallows this iteration of From Hell from ever reaching the heights of the comic counterpart. One of the most famous Jack the Ripper quotes is “One day men will say I gave birth to the 20th century”, a notion that Moore’s Ripper wrestles with throughout the narrative. Indeed, having visions of the multiple wars and atrocities of the coming 100 years would probably ruin your day. “The century was indeed a stage for the dark impulses of the soul,” Roger Ebert wrote in his review of the film, “and recently I’ve begun to wonder if Jack didn’t give birth to the 21st century, too. Twins.”

Working this into From Hell results in some of the most genius storytelling of Moore’s largely-genius career. When William Gull — this story’s assertion of the true identity of Jack — treads down a back alley with the intent of murdering Annie Chapman, he passes a man closing the shades of his tenement:

Gull is granted a flash of the future, seemingly spawned by his violent will. Chapman is his second victim, and his visions of the coming century increase from TVs and Marilyn Monroe posters to hallucinations of far greater profundity. Upon the slaughter of Kate Eddowes he sees what the once-careful architecture of London will eventually give way to:

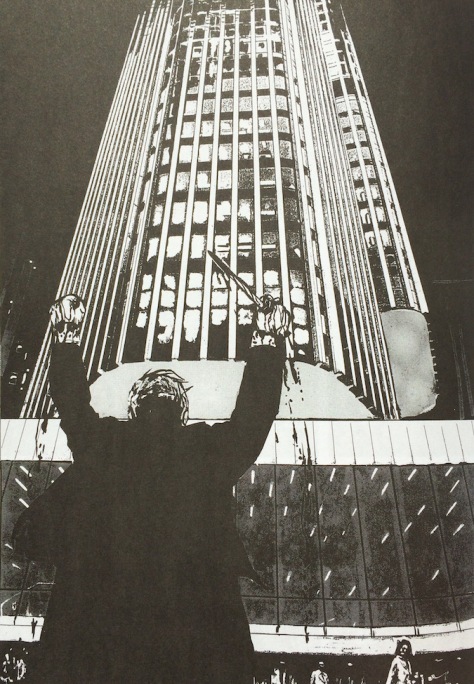

And finally, during the systematic mutilation of final victim Marie Kelly, Gull is transported from the Whitechapel ghetto of 1888 to a gleaming office building of our current era:

“Your own flesh is made meaningless to you.” The disaffectedness and disillusionment of the modern world is intricately entwined in Moore’s narrative, despite it being set in the Victorian Era, yet the same cannot be said of the FH film. These great leaps through time do more than herald the wars and bombs and terrorist attacks and senseless killings populating today’s media. They effectively make Jack’s murders more than simply murders, make them into the gateway through which the waters of violence might come to slowly erode human nature itself. Gull believes his work to be work that will live on well past his mortal life, and each time-launch proves him right.

Excluding these is necessary to uphold the film’s conceit of a more traditional murder-mystery narrative, as we’d have to know Gull to be the Ripper in order to experience these hallucinations with him. Still, considering that this is one such visual flourish that can be accomplished in a medium besides comics, the exclusion serves as the prime representation of the difference in ambition in the work of Moore/Campbell as opposed to Hughes/Hughes. Frankly, comparing the two side-by-side makes the mere term “ambition” seem outsized praise with regards to the movie. The From Hell adaptation is not entirely devoid of visual prowess, particularly with regard to Abberline’s perception of things:

But it’s nowhere near enough to make From Hell into a transcendent experience worthy of the source material. Carpenter notes the importance of the ornate language of Gull’s soliloquy in the scene from the comic above, but the aspect that immediately sticks in the mind is the visual one. It’s jarring, the shift from grimy 1888 to shiny 1988. It brings the terrifying notion of Jack the Ripper operating right now, just around the corner, his hellish enterprise having run itself for a hundred years without any sign of slowing. The film lacks this immediacy: this is 1888, another world, long ago, of little concern today. Ironically that oversight sort of proves Moore’s thesis, we being what Gull calls “a culture grown disinterested even in its own abysmal wounds”, happy to enjoy a Ripper yarn as a simple murder mystery, living in the house that Jack built while pretending that we don’t.

3 thoughts on “From Hell (2001)”