I never much expected Yorgos Lanthimos to become a great filmmaker. He was always a very good filmmaker, and it must be noted that we’re reserving the term great here for someone truly deserving of the moniker, as in one of the all-time greats. Nowadays great gets bandied about a lot. Is Ridley Scott great? From time to time, sure. Maybe we weigh the greatness of Blade Runner against the decidedly-not-so-greatness of Alien: Covenant? Is Francis Ford Coppola great? He definitely was. Does he get a lifetime pass for Godfather and Apocalypse Now? Is Wes Anderson great? No, he’s not. Stylish, yes. Symmetrical, very. But a mere few living filmmakers are transcendently, naturally, consistently great. Surely it’s a malleable and transient label, fit to be removed, re-earned, reconsidered. And surely — as The Dude would say in that movie by the great Coen Brothers — it’s just, like, your opinion, man.

I never much expected Yorgos Lanthimos to become a great filmmaker. He was always a very good filmmaker, and it must be noted that we’re reserving the term great here for someone truly deserving of the moniker, as in one of the all-time greats. Nowadays great gets bandied about a lot. Is Ridley Scott great? From time to time, sure. Maybe we weigh the greatness of Blade Runner against the decidedly-not-so-greatness of Alien: Covenant? Is Francis Ford Coppola great? He definitely was. Does he get a lifetime pass for Godfather and Apocalypse Now? Is Wes Anderson great? No, he’s not. Stylish, yes. Symmetrical, very. But a mere few living filmmakers are transcendently, naturally, consistently great. Surely it’s a malleable and transient label, fit to be removed, re-earned, reconsidered. And surely — as The Dude would say in that movie by the great Coen Brothers — it’s just, like, your opinion, man.

Lanthimos isn’t yet one of the all-time greats, but watching The Favourite I did think, for the first time, that he might just have it in him someday. Such a consideration might have been questionable after his previous film The Killing of a Sacred Deer, an overly melancholy tale featuring a creepy turn from Barry Keoghan, one cool shot of a descending escalator, a Funny Games-esque climax and a whole bunch of monotone dialogue. It wasn’t a bad movie, and it might even be a pretty good movie. But the cold design of Sacred Deer made it impactful but never resonant. Maybe it was just so different than The Lobster, the previous effort from Lanthimos, which was a darkly funny and much more inventive film.

Boasting a “return to roots” formula meant to appeal to champions of

Boasting a “return to roots” formula meant to appeal to champions of

It would have been easy for Shoplifters to glamorize the criminal acts of its central characters. Hirokazu Kore-eda’s latest film follows an impoverished Tokyo family surviving on a hierarchical system of thievery, nicking small items where the opportunity arises or, more frequently, setting out on an express mission to steal that which they need. The setup, of course, is worlds away from the heist genre, but it’s still refreshing to experience these criminal acts for what they actually are: desperate, thrill-less acts devoid of meticulous planning or grifter’s luck. And if there is any thrill in stealing shampoo and ramen noodles, it’s a thrill that quickly sinks into the pit of one’s stomach, weighed by the immorality of it all.

It would have been easy for Shoplifters to glamorize the criminal acts of its central characters. Hirokazu Kore-eda’s latest film follows an impoverished Tokyo family surviving on a hierarchical system of thievery, nicking small items where the opportunity arises or, more frequently, setting out on an express mission to steal that which they need. The setup, of course, is worlds away from the heist genre, but it’s still refreshing to experience these criminal acts for what they actually are: desperate, thrill-less acts devoid of meticulous planning or grifter’s luck. And if there is any thrill in stealing shampoo and ramen noodles, it’s a thrill that quickly sinks into the pit of one’s stomach, weighed by the immorality of it all.

You could call Roma the most colorful black-and-white film ever made. After the Centerpiece screening at the 56th New York Film Festival, writer/director Alfonso Cuarón noted how important the visual presentation was to the overall effect of the movie. Crucial among his points was that this black-and-white is “not a nostalgic black-and-white” but instead “modern” and “pristine,” disabusing the viewer of the notion that this tale is unfolding in a long-forgotten place or time. Despite being assured throughout the film that the place is Mexico City and the year is 1971, Roma simultaneously manages to assure you that what’s happening is happening here and now.

You could call Roma the most colorful black-and-white film ever made. After the Centerpiece screening at the 56th New York Film Festival, writer/director Alfonso Cuarón noted how important the visual presentation was to the overall effect of the movie. Crucial among his points was that this black-and-white is “not a nostalgic black-and-white” but instead “modern” and “pristine,” disabusing the viewer of the notion that this tale is unfolding in a long-forgotten place or time. Despite being assured throughout the film that the place is Mexico City and the year is 1971, Roma simultaneously manages to assure you that what’s happening is happening here and now.

After winning the People’s Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival last weekend, public opinion on Green Book quickly pivoted from a general curiosity in a dramatic effort from the guy who did Dumb and Dumber to genuine anticipation for an early Oscar frontrunner. The film’s first trailer, full of emotional monologues and swelling orchestral strings, already gave off a For Your Consideration vibe before Green Book even premiered. But TIFF has certainly become a stronger indicator of awards season success in recent years, and nine of the last ten People’s Choice Award winners went on to become Best Picture nominees. Universal went into overdrive this past week to get their sudden contender out to smaller festivals and screenings, so this week’s presentation at the 34th Boston Film Festival was a pleasant surprise.

After winning the People’s Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival last weekend, public opinion on Green Book quickly pivoted from a general curiosity in a dramatic effort from the guy who did Dumb and Dumber to genuine anticipation for an early Oscar frontrunner. The film’s first trailer, full of emotional monologues and swelling orchestral strings, already gave off a For Your Consideration vibe before Green Book even premiered. But TIFF has certainly become a stronger indicator of awards season success in recent years, and nine of the last ten People’s Choice Award winners went on to become Best Picture nominees. Universal went into overdrive this past week to get their sudden contender out to smaller festivals and screenings, so this week’s presentation at the 34th Boston Film Festival was a pleasant surprise.

Shane Black’s new Predator movie, which opened last night and was advertised as an “explosive reinvention” of the series, purportedly debuts on the crest of a new wave of R-rated Hollywood blockbusters. Deadpool and Logan did pretty well in ’16 and ’17, see, and

Shane Black’s new Predator movie, which opened last night and was advertised as an “explosive reinvention” of the series, purportedly debuts on the crest of a new wave of R-rated Hollywood blockbusters. Deadpool and Logan did pretty well in ’16 and ’17, see, and

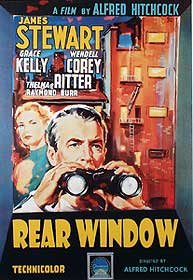

Alfred Hitchcock was no stranger to the optical point-of-view shot, inserting a camera into the heads of his characters in nearly every film throughout his career. The Master of Suspense knew that this shortcut to conveying a character’s experience could be a powerful tool if used artfully. In Vertigo, this artfulness resulted in one of the greatest POV shots of all time, the discombobulating push-in-zoom-out (technically a “dolly zoom”) that simultaneously suggests our hero’s unbalanced frame of mind. More importantly, Hitchcock routinely tied these POV shot choices to significant narrative moments. In Vertigo this served to heighten the most intense action scenes by placing us directly in the action; elsewhere, the POV shot served to convey vital information, revelations, twists and — you guessed it! — suspense:

Alfred Hitchcock was no stranger to the optical point-of-view shot, inserting a camera into the heads of his characters in nearly every film throughout his career. The Master of Suspense knew that this shortcut to conveying a character’s experience could be a powerful tool if used artfully. In Vertigo, this artfulness resulted in one of the greatest POV shots of all time, the discombobulating push-in-zoom-out (technically a “dolly zoom”) that simultaneously suggests our hero’s unbalanced frame of mind. More importantly, Hitchcock routinely tied these POV shot choices to significant narrative moments. In Vertigo this served to heighten the most intense action scenes by placing us directly in the action; elsewhere, the POV shot served to convey vital information, revelations, twists and — you guessed it! — suspense:

If you’re a connoisseur of modern helicopter cinema, then Mission: Impossible – Fallout is the event of the season. Not since Black Hawk Down has the Neo-Copterism movement asserted such a well-defined visual aesthetic, such elevated narrative and tonal language, such awesome fucking explosions. Everything a refined and learned copterhead cinephile could possibly desire finds fresh life here. There is an absurdist, Lynchian quality infused into the rhythmic weaving of two whirlybirds; there are rarefied, Brechtian attributes present in those characters left on the ground. There is a continuation of the leitmotif established in the first Mission: Impossible‘s chopper-chase finale. When read through the lens of the tenets of cinéma vérité, Fallout delivers a powerful indictment of those who don’t actually know how to fly such a machine. And, in a move sure to receive recognition come awards season, auteur director Christopher McQuarrie playfully inverts the male gaze by literally flipping Tom Cruise upside down in a helicopter.

If you’re a connoisseur of modern helicopter cinema, then Mission: Impossible – Fallout is the event of the season. Not since Black Hawk Down has the Neo-Copterism movement asserted such a well-defined visual aesthetic, such elevated narrative and tonal language, such awesome fucking explosions. Everything a refined and learned copterhead cinephile could possibly desire finds fresh life here. There is an absurdist, Lynchian quality infused into the rhythmic weaving of two whirlybirds; there are rarefied, Brechtian attributes present in those characters left on the ground. There is a continuation of the leitmotif established in the first Mission: Impossible‘s chopper-chase finale. When read through the lens of the tenets of cinéma vérité, Fallout delivers a powerful indictment of those who don’t actually know how to fly such a machine. And, in a move sure to receive recognition come awards season, auteur director Christopher McQuarrie playfully inverts the male gaze by literally flipping Tom Cruise upside down in a helicopter.

In many instances a film is like a con: it wants to hook you, it wants to make you personally invested in the outcome, and it wants you to walk away with a smile on your face and slightly less in your wallet. If the endeavor is a success, there will always be enough to suggest that the artist — the film artist or the con artist — knows a truth that you do not. If the endeavor is unsuccessful, the feeling of being cheated will linger and frustrate.

In many instances a film is like a con: it wants to hook you, it wants to make you personally invested in the outcome, and it wants you to walk away with a smile on your face and slightly less in your wallet. If the endeavor is a success, there will always be enough to suggest that the artist — the film artist or the con artist — knows a truth that you do not. If the endeavor is unsuccessful, the feeling of being cheated will linger and frustrate.