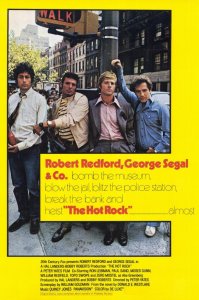

Here’s the starting lineup: William Goldman, red-hot off his Oscar win for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, is your screenwriter. He’s adapting a novel by Donald E. Westlake, whose protagonist John Dortmunder will soon become one of his most popular creations. Robert Redford plays Dortmunder, with George Segal cast as his right-hand man. And you’ve got Peter Yates (Bullitt, The Friends of Eddie Coyle) in the director’s chair, seeking to marry his sensibilities for comedy and crime in the same film. Top it off with Quincy Jones for the score, and The Hot Rock should be shaping up to be a hell of a film.

One can understand and appreciate the drive to make a lighthearted caper in early ’70s New York, when the crime genre was growing in popularity but also in self-seriousness. Dirty Harry did much to cement a gritty remorselessness in the genre in 1971, asserting an edgy protagonist with no reservations about killing his enemies. In March 1972, The Godfather would in turn spawn a million imitators looking to recapture the Very Serious Drama of American crime. So the conceit of The Hot Rock, at the time, was explicit: bring back the fun.

Continue reading The Hot Rock (1972)

The first scene of E.T. wouldn’t be the same in any other medium. Wordless, shadowy and purposefully obscure, there’s still a ton of information conveyed through visuals alone. Spielberg was (and maybe still is) a fan of this kind of opening, eschewing expository positioning in favor of details that might strike as somewhat disorienting at first. There are fifteen or so characters here, all of them faceless. But even though we don’t get an instance of “Spielberg Face” — his beloved reaction shot of a wonderstruck visage, eyes wide, mouth agape — there’s still plenty to gawk at in these few short minutes.

The first scene of E.T. wouldn’t be the same in any other medium. Wordless, shadowy and purposefully obscure, there’s still a ton of information conveyed through visuals alone. Spielberg was (and maybe still is) a fan of this kind of opening, eschewing expository positioning in favor of details that might strike as somewhat disorienting at first. There are fifteen or so characters here, all of them faceless. But even though we don’t get an instance of “Spielberg Face” — his beloved reaction shot of a wonderstruck visage, eyes wide, mouth agape — there’s still plenty to gawk at in these few short minutes.

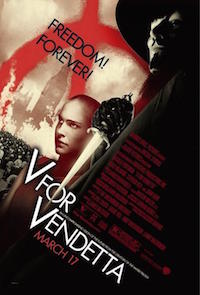

A lot of what Alan Moore has created is now considered classic. V for Vendetta, League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, From Hell, The Killing Joke, his run on Swamp Thing…to say this stuff is at the vanguard of comic-book storytelling is to undermine the fact that this stuff is the vanguard of comic-book storytelling. But it’s important to remember — crucial, actually — that Moore’s never purposefully written a “classic,” meaning his tales are almost exclusively nontraditional narratives that toy with genre and literary consciousness. The writer has a few reasons to despise Hollywood, but the primary point of contention must be that each film adaptation of his comics seems to shove the original tale back into a traditional, classic structure. It happened with

A lot of what Alan Moore has created is now considered classic. V for Vendetta, League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, From Hell, The Killing Joke, his run on Swamp Thing…to say this stuff is at the vanguard of comic-book storytelling is to undermine the fact that this stuff is the vanguard of comic-book storytelling. But it’s important to remember — crucial, actually — that Moore’s never purposefully written a “classic,” meaning his tales are almost exclusively nontraditional narratives that toy with genre and literary consciousness. The writer has a few reasons to despise Hollywood, but the primary point of contention must be that each film adaptation of his comics seems to shove the original tale back into a traditional, classic structure. It happened with

What’s the worst thing that can happen in sports? That’s the question voiced by the title character as the curtain goes up on Molly’s Game, Aaron Sorkin’s directorial debut and latest produced screenplay since 2015’s

What’s the worst thing that can happen in sports? That’s the question voiced by the title character as the curtain goes up on Molly’s Game, Aaron Sorkin’s directorial debut and latest produced screenplay since 2015’s

The Black Stallion is very much a film of two halves. You could enter the film at the midpoint and still enjoy the back 50% as a self-contained story. Similarly, you could just watch the first chunk and then turn it off feeling surprisingly satisfied. Viewed as a whole, though, Stallion serves as a personality quiz centered around whichever half you ultimately prefer. Think Full Metal Jacket or King Kong, which not only bring characters through two vastly different settings but seemingly bring them through different genres of film as well. It’s possible to enjoy the whole film in each of these instances, but by design one segment probably connects with you more powerfully than the other.

The Black Stallion is very much a film of two halves. You could enter the film at the midpoint and still enjoy the back 50% as a self-contained story. Similarly, you could just watch the first chunk and then turn it off feeling surprisingly satisfied. Viewed as a whole, though, Stallion serves as a personality quiz centered around whichever half you ultimately prefer. Think Full Metal Jacket or King Kong, which not only bring characters through two vastly different settings but seemingly bring them through different genres of film as well. It’s possible to enjoy the whole film in each of these instances, but by design one segment probably connects with you more powerfully than the other.

Today, the Fifth of November, is the perfect day for V for Vendetta. To be sure, Guy Fawkes Day finds a reference or two in a story about an anarchist in a Guy Fawkes mask. Go figure. He even intones as much: Remember, remember, the Fifth of November. But it’s this particular 11/5, the one here in 2017, that’s a perfect day for V. Because we’re now coming up on a year (!) since the presidential election of 2016, an entire year of what this masked anarchist, vested with a vast and verbose vocabulary, would call vitriol, venom, vilification, violence.

Today, the Fifth of November, is the perfect day for V for Vendetta. To be sure, Guy Fawkes Day finds a reference or two in a story about an anarchist in a Guy Fawkes mask. Go figure. He even intones as much: Remember, remember, the Fifth of November. But it’s this particular 11/5, the one here in 2017, that’s a perfect day for V. Because we’re now coming up on a year (!) since the presidential election of 2016, an entire year of what this masked anarchist, vested with a vast and verbose vocabulary, would call vitriol, venom, vilification, violence.