In the climactic finale of Annihilation, there is a moment in which a shape-shifting alien bioclone with burning arms lovingly embraces a charred corpse in a lighthouse that has been struck by a meteor and overtaken by a mutated blight that threatens all life as we know it. Go ahead and read that sentence again if you have to. I dare you to try to come up with something so outlandish, so unsettling, so straight-up weird, much less deploy it at a crucial moment in a multimillion-dollar motion picture production. We live in a time where pretty much every sci-fi film with a budget this size (about $40 million) ends one way: explosions. The scripts all contain the same line: Big CGI Thing bursts into CGI flame. Heck, explosions probably typify the finale of most Hollywood films, sci-fi or otherwise, and the scripts for their inevitable sequels all contain the same line: Bigger CGI Thing bursts into bigger CGI flame.

In the climactic finale of Annihilation, there is a moment in which a shape-shifting alien bioclone with burning arms lovingly embraces a charred corpse in a lighthouse that has been struck by a meteor and overtaken by a mutated blight that threatens all life as we know it. Go ahead and read that sentence again if you have to. I dare you to try to come up with something so outlandish, so unsettling, so straight-up weird, much less deploy it at a crucial moment in a multimillion-dollar motion picture production. We live in a time where pretty much every sci-fi film with a budget this size (about $40 million) ends one way: explosions. The scripts all contain the same line: Big CGI Thing bursts into CGI flame. Heck, explosions probably typify the finale of most Hollywood films, sci-fi or otherwise, and the scripts for their inevitable sequels all contain the same line: Bigger CGI Thing bursts into bigger CGI flame.

But Annihilation goes a long way to assuaging the bitterness now associated with what the Hard Sci-Fi genre has threatened to become, and writer/director Alex Garland might just be the beacon of hope in this regard. It was already clear that Garland’s a formidable painter, but it’s still special to see a wider canvas filled with such vibrant colors. His debut directing gig Ex Machina knocked it out of the park (and is in some senses a superior film), but with Annihilation he gets more characters, more locations, more visual effects and more freedom to tell the story his way.

I arrived late to the party for The Shape of Water, having finally caught the movie a few weeks ago after months and months of dodging reviews online. Guess I’d better add my voice to the fray, huh? Maybe a piece on how writer/director Guillermo del Toro’s creativity allowed him to get away with a smaller budget…but, no,

I arrived late to the party for The Shape of Water, having finally caught the movie a few weeks ago after months and months of dodging reviews online. Guess I’d better add my voice to the fray, huh? Maybe a piece on how writer/director Guillermo del Toro’s creativity allowed him to get away with a smaller budget…but, no,

There’s nothing quite like a good movie villain. If we’re talking about the Marvel Cinematic Universe, maybe you read this statement another way: there’s nothing quite like a good movie villain, anywhere. With the exception of Loki and a few other superbaddies, the MCU’s well-documented track record for weak villains has been the franchise’s persistent shortcoming. In much the same way as the villains of the Bond franchise became less and less interesting with each progressive installment, by this point you basically know what you’re getting in the Antagonist Department. At worst, the MCU gives us a paper-thin doppelgänger for the hero, a bland apocalypse-seeker with vague motivation, or whatever the heck Christopher Eccleston was supposed to be in Thor: The Dark World. At best, the MCU just gives us Loki for like the fifth time.

There’s nothing quite like a good movie villain. If we’re talking about the Marvel Cinematic Universe, maybe you read this statement another way: there’s nothing quite like a good movie villain, anywhere. With the exception of Loki and a few other superbaddies, the MCU’s well-documented track record for weak villains has been the franchise’s persistent shortcoming. In much the same way as the villains of the Bond franchise became less and less interesting with each progressive installment, by this point you basically know what you’re getting in the Antagonist Department. At worst, the MCU gives us a paper-thin doppelgänger for the hero, a bland apocalypse-seeker with vague motivation, or whatever the heck Christopher Eccleston was supposed to be in Thor: The Dark World. At best, the MCU just gives us Loki for like the fifth time.

Of the nine Best Picture nominees at this year’s Academy Awards, four of them — that’s a healthy 44% — address predatory love. Okay, maybe only three if you don’t include The Shape of Water, though, technically, yes, the protagonist is in love with a literal predator. Down to 33%, which is still a higher percentage than you’d expect from American awards season. Though I suppose Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri is never really about rape, only using that (as it used a number of other social issues) as a springboard for dramatic explorations of entirely different social issues. So, okay, fine: 22%.

Of the nine Best Picture nominees at this year’s Academy Awards, four of them — that’s a healthy 44% — address predatory love. Okay, maybe only three if you don’t include The Shape of Water, though, technically, yes, the protagonist is in love with a literal predator. Down to 33%, which is still a higher percentage than you’d expect from American awards season. Though I suppose Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri is never really about rape, only using that (as it used a number of other social issues) as a springboard for dramatic explorations of entirely different social issues. So, okay, fine: 22%.

Early on in Phantom Thread I started thinking about the miniaturized nature of certain segments in the cinema of Paul Thomas Anderson. At the top of this latest film we see Reynolds Woodcock’s morning routine, clearly practiced to the point of automation, nearly mechanical, though the whole scene lasts less than thirty seconds. He shaves, he slicks his hair, he pulls on his big winecolored socks, his pants. And that’s it. The dressmaker is dressed. One might expect a little more extravagance from a film that’s ostensibly about high-end style and tailored beauty, no?

Early on in Phantom Thread I started thinking about the miniaturized nature of certain segments in the cinema of Paul Thomas Anderson. At the top of this latest film we see Reynolds Woodcock’s morning routine, clearly practiced to the point of automation, nearly mechanical, though the whole scene lasts less than thirty seconds. He shaves, he slicks his hair, he pulls on his big winecolored socks, his pants. And that’s it. The dressmaker is dressed. One might expect a little more extravagance from a film that’s ostensibly about high-end style and tailored beauty, no?

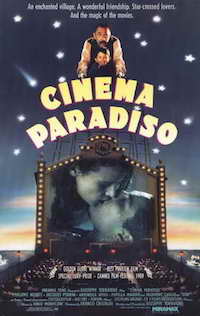

I’m not a big crier, but an exception can usually be made for Cinema Paradiso. I wasn’t too much older than young Toto when I first saw the film, and I held it together until the very end when a middle-aged Toto sits in reverent silence to watch the film left behind by his departed friend Alfredo. The film is a patchwork of clips deemed too pornographic by the village priest, kisses and sexual advances and tender embraces from dozens of different movies, cut and discarded for the sake of public decency. It is a mosaic of passion, free of dialogue, cobbled together by a blind man as a reminder of the place where Toto’s own passions were born. It brings him backwards in time. And if you’re Toto or a big baby like me, it’s a real tearjerker.

I’m not a big crier, but an exception can usually be made for Cinema Paradiso. I wasn’t too much older than young Toto when I first saw the film, and I held it together until the very end when a middle-aged Toto sits in reverent silence to watch the film left behind by his departed friend Alfredo. The film is a patchwork of clips deemed too pornographic by the village priest, kisses and sexual advances and tender embraces from dozens of different movies, cut and discarded for the sake of public decency. It is a mosaic of passion, free of dialogue, cobbled together by a blind man as a reminder of the place where Toto’s own passions were born. It brings him backwards in time. And if you’re Toto or a big baby like me, it’s a real tearjerker.

Charley Varrick is one lucky guy. Odd, maybe, to associate “luck” with a man who botches a robbery and gets his wife killed, and odder still once he discovers that the money he does get away with belongs to the ruthless Mafia. Over the course of Charley Varrick poor Charley buries his wife, runs from the police, runs from the Mafia, loses his partner, loses his house, loses his plane, and spends a heck of a lot of time contending with the incompetence of others. Traditionally we call the person in this string of situations “unlucky.”

Charley Varrick is one lucky guy. Odd, maybe, to associate “luck” with a man who botches a robbery and gets his wife killed, and odder still once he discovers that the money he does get away with belongs to the ruthless Mafia. Over the course of Charley Varrick poor Charley buries his wife, runs from the police, runs from the Mafia, loses his partner, loses his house, loses his plane, and spends a heck of a lot of time contending with the incompetence of others. Traditionally we call the person in this string of situations “unlucky.”

One of the previews that screened before last night’s Boston premiere of Blade Runner 2049 was for next year’s monsters vs. robots actioner Pacific Rim Uprising, an inevitable if somewhat tardy sequel to Guillermo del Toro’s 2013 original. Based solely on this trailer, it’s evident that Uprising centers on the son of the first film’s protagonist, alludes heavily to that first film, and possibly just revamps the plot with slightly louder explosions. I was reminded, regrettably, of Independence Day: Resurgence, which gave off a similar reek of franchise desperation.

One of the previews that screened before last night’s Boston premiere of Blade Runner 2049 was for next year’s monsters vs. robots actioner Pacific Rim Uprising, an inevitable if somewhat tardy sequel to Guillermo del Toro’s 2013 original. Based solely on this trailer, it’s evident that Uprising centers on the son of the first film’s protagonist, alludes heavily to that first film, and possibly just revamps the plot with slightly louder explosions. I was reminded, regrettably, of Independence Day: Resurgence, which gave off a similar reek of franchise desperation.

Prolific director Ben Wheatley followed up 2015’s

Prolific director Ben Wheatley followed up 2015’s

I recently watched Edgar Wright’s Hot Fuzz for the zillionth time. This was partly to assuage my excitement for Baby Driver, Wright’s latest, and partly because the discovery of a commentary track by Wright and his buddy Quentin Tarantino was too good to pass up. Usually commentary tracks feel slight, strained, straight-up unnecessary; Wright and Tarantino have a casual chat that’s nearly as bonkers as Hot Fuzz itself. The pair share a vast encyclopedic knowledge of film and music, and throughout the course of the commentary they discuss nearly 200 films — basically everything besides Hot Fuzz — and if you’re thinking someone should write out that list, well, yeah:

I recently watched Edgar Wright’s Hot Fuzz for the zillionth time. This was partly to assuage my excitement for Baby Driver, Wright’s latest, and partly because the discovery of a commentary track by Wright and his buddy Quentin Tarantino was too good to pass up. Usually commentary tracks feel slight, strained, straight-up unnecessary; Wright and Tarantino have a casual chat that’s nearly as bonkers as Hot Fuzz itself. The pair share a vast encyclopedic knowledge of film and music, and throughout the course of the commentary they discuss nearly 200 films — basically everything besides Hot Fuzz — and if you’re thinking someone should write out that list, well, yeah: